Free to Grieve After Juneteenth

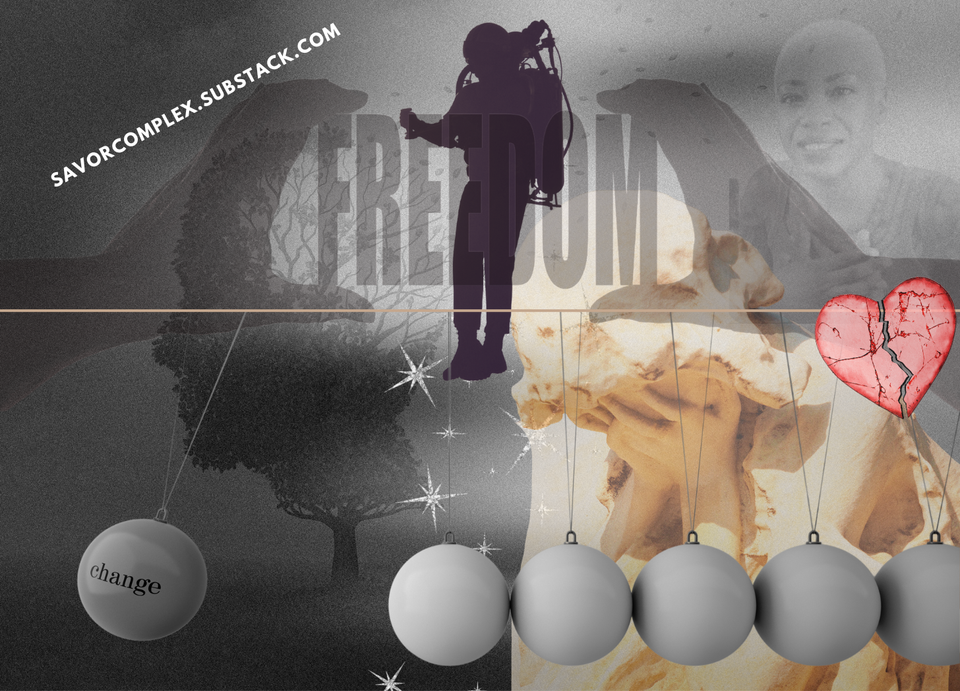

Exactly 71 years and seven days after the origins of Juneteenth in 1865, a person I love dearly was born. I found myself reflecting on their recent shift from fierce, hard-earned independence to being told something that effectively limits their independence, overshadows their freedom, and plays out like the opposite of joy.

This person’s shift from independence to needing around-the-clock care due to the aging process and the changes that come with it, have been a turbo jet-pack on my recent studies on loss, on intergenerationality, on aging, on dying, on grief. Grief is how we savor loss (remember?), and while some losses are fast and furious, there are some, like this kind, that are slow and sporadic, spiky and persistent.

When a close family member is diagnosed with dementia there are layers of slow-ass moving grief. And I’m not speaking from a place of theory; I have experienced this personally, am experiencing it personally.

There is, for me, a sense of panic, like ‘How did I miss it? How come I didn't see it sooner?’ Shit like that. Then there's also the reality of experiencing the person who was diagnosed, being given that diagnosis. I see them going through that experience, while having lots of lucid moments to process what is happening to their brain, to process the part of aging that can happen, and is happening to them.

There's also the people who care for that person, and how it changes our lives, in terms of everything from the logistical and financial elements of a different type of care for that person. That person who was recently independent, living on their own, going out to shop for food to eat and yarn to knit! Their independence was accented by regular check-ins from various people in the family, some in person, others by phone. And now, they must live with one of us and be cared for, even if we are working outside the home or working from home and can't give them consistent attention. We changed, some of us much more than others, what our daily lives look like to now include the attention and care to this family member who's been diagnosed.

Then there's the type of care that each of this person's caregivers will need. They'll need to tag other family members in to do other tasks like following up with a doctor, or tracking a particular insurance verification process so that more in-home care can be covered under the insurance. Scheduling time to come see this person and give their primary caregivers some relief so that they can go out of town for a few days, have time to themselves, and to other people and projects that are important to them and that need attending to as well.

And in all of that, each person who loves the person who was diagnosed is also facing, a little bit more directly, their own mortality, their own genetic predispositions. The people born after us, our children, or nieces and nephews, or young people in our lives who would be in the position that we’re in now. Who will be the people who are affected by whatever diagnosis you or I may get if we get to age?

Each of us are now facing that a little bit more directly and perhaps in conversation around that. We are bringing it up in our conversations with other friends and collaborators. ‘Hey, have you talked with your people about, or have you thought about a dementia care plan? or an Alzheimer's care plan?’ Things we probably weren’t thinking (as much) about a year ago.

Then there's the anticipatory grief of being that person, or having it happening even closer to home than the family member that's experiencing it now. Maybe going into a sense of newer urgency or attention around what you can do now from where you are now, with all the mental capacity that you currently have now. Perhaps seeing it as a privilege to have this level of mental capacity, and attempting to make sure that you use it to minimize the weight and pressure on the people who (we hope) will care for us as we (if we) age.

So, when we talk about the layers of grief, we're talking about so much more than the death of a physical body. We are also talking about all these other types of grief, including all the spin-off grief that we might be experiencing and don't even recognize it. When we don’t recognize grief, we are hard on ourselves when we can't operate how we're used to operating, or how we want to operate.

When we do recognize the presence of grief, we can each say, Oh, no wonder I'm frustrated and can't get a handle on this particular thing! I'm grieving! (taken from my notes from the ILID Grief Course)

And if we can become more knowledgeable about grief, more grief literate, then imagine how much more space and grace might we offer ourselves and people around us who are also grieving.

Member discussion