Black Woman, Big Talk, Small Island.

When Black women from small islands talk big (critical) talk about culture and community, some people feel us, and feel relieved. Others will blame us and wish for our silence. I look forward to being felt, I ain’t afraid of blame, and silence surely is not my ministry.

In this book, I cover a seven-year span of time in four parts, using stories, essays, and processes to examine relationships to culture, parenting, community, and education.

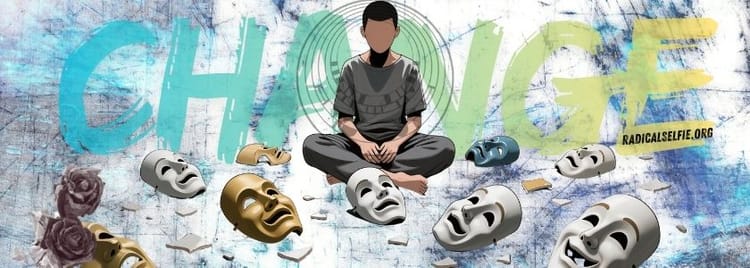

Each part invites parents and (other) educators into a personal leadership process that is part archivist, part futurist because we must archive some aspects of ourselves once we designate it as an artifact. In doing so, it is named as part of the history of us, and in designating it as historical, we can disconnect our present and future selves from it in important, lasting ways.

The process creates an encasing that offers clear delineation and deliberate separation of self from artifact. This is done so that, as an example, my specific history of hitting my children is no longer something that I associate with this me, or future me. It has been outmoded, acknowledged as something that was part of the world that I was born into. The environment, a culture, that I as the me that I am now, recognize as not inextricably connected to me in my present and future forms. This designation anchors it only to my past, archiving it and rendering it inaccessible as a tool to use today.

Black Bear |Wild Weed (BB|WW) begins with a story about a funeral, mine. It begins with an end, and then weaves us back to a beginning, inviting us to sort and shed, to gather and gain, to re-member and to release.

I share the rationale behind the funeral I had in 2019, a few months after my experience with Grandmother Plant, Ayahuasca. The pandemic began shortly after that year ended, and so I had little time to mourn and to integrate.

Now, almost two years later, I discovered that there was more work to be done; post-mortem work that included artifact naming and vital archiving work. That work and its results are detailed in this text.

In BB|WW, I tell stories about my partner and I as Jamaican-born people who remained connected to our culture when our parents moved us to America. We lived in a southern U.S. community that still held a lot of Jamaican people and values. And then we also were able to go back to Jamaica as adults, with our children for about five or six years, spending between two to six months at a time there. Really, that's where a lot of the distinctions, the disentanglement and affirming elements of our relationship to our origin cultures began to be really visible to us. We noticed that some aspects of our culture we embraced and wanted to continue to embody. Others we were wrestling with, and others got straight-up outmoded, we archived ‘em.

You’ll read about things that I archived, as in things that are designated as artifacts, and how I got to the personal definitions of archives and artifacts that I offer today.

I'm telling stories about four aspects of my origin culture that my partner, Kris, and I were able to tap into as rites of passage that impacted our daughters' lives as first-generation Americans.

We didn't stay in Jamaica into adulthood, or even our teen years. We left as children (I was 10) and because of that, we got a particular slice of perspective, a vantage point, so to speak. We were able to get a bit of distance from elements of the culture as young Jamaicans being geographically and politically in America, but very much steeped and governed inside the home and in community, in Jamaican cultural norms.

That changed in our late teens, when he and I (separately) moved to other places for college. We both ended up in places where Jamaican culture was not as prominent as our K-12 locales. And then, within less than a decade of doing that, we became parents in the US South. Black parents from a Black nation, raising American children in the US South.

For me, experiences with anti-blackness in the US South caused me to begin noticing how some aspects of the other types of prejudice and ignorance that I experienced felt madd connected to the some shit I was complicit in because I went along without questioning some aspects of my origin culture. That led me to archiving work.

So, we talkin bout archive the verb, the act.

We talkin bout artifact the noun, a thing made up by a human.

By artifacts, I mean things that can be designated as historical tools, weapons, ornaments made or shaped by human hand or mind.

By archiving, I mean the gathering of historical materials kept and preserved for human interest, so that people may know those things existed.

Archiving names particular things as part of a history that we did not choose in this conscious time and space. Just one that we had close proximity to because it was and is embedded in our origin cultures. And as it turns out, we are not solely made up of our cultural artifacts, because our design updates, and those updates include the ones we consciously choose.

And so this is a guidebook for the migration journey of folk who are noticing our own rootboundness, their own unexamined or examined yet still tethered to aspects of their history through their cultural backgrounds.

More next week…

Feeling it? Please share with a homie who might feel it too!

Member discussion